February 28, 2024

Being able to easily get from the house to the playground affects how long and how often children use an adapted ride-on car, according to a study, Off to the park: a geospatial investigation of adapted ride-on car usage, published by CREATE Ph.D. student Mia Hoffman with CREATE associate director Heather A. Feldner, who is the lead researcher on the project. Their research demonstrates the importance of accessibility in the built environment and that advocating for environmental accessibility should include both the indoors and outdoors.

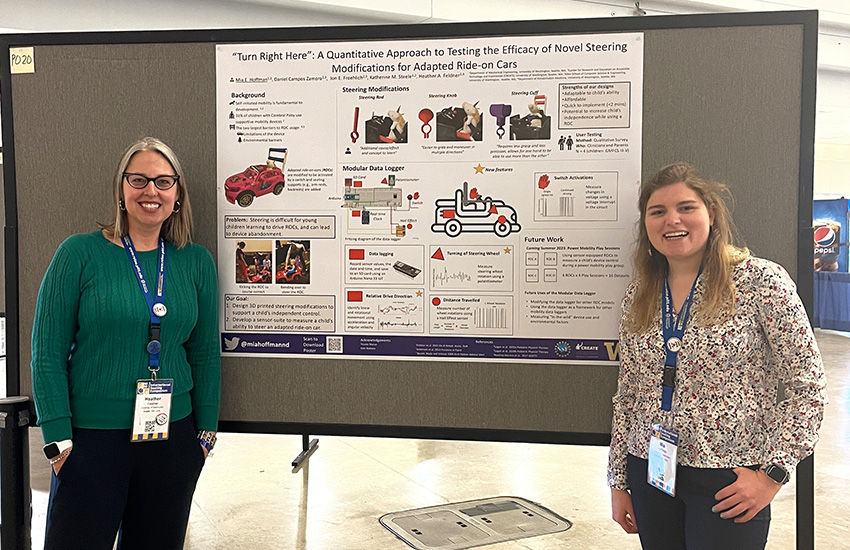

For a recent study, adapted ride-on cars were provided to 14 families with young children in locations across Western Washington. Photo courtesy of Heather Feldner.

Ride-on cars are miniature toy cars for children with steering wheels and a battery-powered pedal. Adapted ride-on cars are an easy-to-use temporary solution for children with mobility issues. Although wheelchairs have more finite control, insurance typically covers new wheelchairs every five years. Children under age 5 can use adapted ride-on cars to explore their surroundings if they outgrow their wheelchair, or if they aren’t able to be in a wheelchair yet.

Exploration is critical to language, social and physical development. There are big benefits when a child starts moving.

Mia Hoffman, CREATE Ph.D. student

“Adapted ride-on cars allow children to explore by themselves,” says Mia Hoffman, the Ph.D. candidate in mechanical engineering who co-authored the paper published in fall 2023. “Exploration is critical to language, social and physical development. There are big benefits when a child starts moving.”

The researchers adapted the ride-on cars to make them more accessible. Instead of a foot pedal, children might start the car with a different option that’s accessible to them, such as a large button or a sip-and-puff, which is a pneumatic device that would respond to air being blown into it. Researchers added additional structural supports to the device, such as a backrest made out of kickboards or PVC side-supports.

Adapted ride-on cars were provided to 14 families with young children in locations across Western Washington. Heather Feldner, an assistant professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and adjunct assistant professor in ME, trained families on how to use the cars. The families then spent a year playing with the cars. Each car had an integrated data logger that tracked how often the child pressed the switch to move the car, and GPS data indicated how far they traveled.

The study found that most play sessions occurred indoors, underscoring the importance of indoor accessibility for children’s mobility technology. However, children used the car longer outdoors, and identifying an accessible route increased the frequency and duration of outside play sessions. Study participants drove outdoors more often in pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods, measured by researchers with the Walk Score, and when close to accessible paths, measured by Project Sidewalk’s AccessScore.

“Families can sometimes be uncertain about introducing powered mobility for their children in these early stages of development,” says Feldner. “But ride-on cars and other small devices designed for kids open up so many opportunities — from experiencing the joy of mobility, learning more about the world around them, enjoying social time with family and friends in new environments, and working on developmental skills. We want to work with kids and families to show them what is possible with these devices, listen to their needs and ideas, and continue working to ensure that both our technology designs and our community environments are accessible and available for all.”

Exploring different mobility devices

As a graduate student, Hoffman conducts research on children ages 3 and under who might crawl, roll, sit up, or cruise in a power mobility device. Besides processing sensor data and other data analysis, Hoffman’s work also involves getting to know families, “playing with a lot of toys, singing, and entertaining kids,” she jokes.

Research involving pediatrics and accessibility like the adapted ride-on cars study is why Hoffman joined the Steele Lab. She became interested in biomechanics in sixth grade, when she learned that working on engineering and medical design was possible. As an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame, Hoffman studied brain biomechanics, computational design and assistive technology. She worked on projects such as analyzing the morphology of monkey brains and creating 3D-printed prosthetic hands for children.

After connecting with Feldner and Kat Steele, Albert Kobayashi Professor in Mechanical Engineering and CREATE associate director, Hoffman realized that the Steele Lab, which often collaborates with UW Medicine, was the perfect fit.

Hoffman is currently working on research with Feldner and Steele that compares children’s usage of a commercial pediatric powered mobility device to their usage of adapted ride-on cars in the community environment. Next, Hoffman will conduct one of the first comparative studies about how using supported mobility in the form of a partial body weight support system or using a powered wheelchair affects children’s exploration patterns. The study involves children with Down Syndrome, who often have delayed motor development and who are underrepresented in mobility research.

There can be stigma associated with using a wheelchair instead of a walker or another mobility device that may help with motor development, but Hoffman says the study could demonstrate that both are important.

“The goal is to show that children can simultaneously work on motor gains while using powered wheelchairs or other mobility devices to explore their environment,” she says.

“Our hope is for kids to just be kids,” says Hoffman. “We want them to be mobile and experience life at the same time as their peers. It’s about meeting a kid where they’re at and supporting them so that they can move around and play with their friends and family.”

This article was excerpted from an article written by Lyra Fontaine for Mechanical Engineering.