Dr. Mankoff, a professor in the Information School and the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, will speak at the UW’s GAAD mid-day program on Thursday, May 15. What initially drew you to the intersection of computing, accessibility, and disability studies? I was a computer scientist first—and then I became disabled. That personal shift made me start thinking about how technology could better meet my needs. My first faculty position was at UC Berkeley, which was at…

Category: inclusion

Funding and training opportunities – Winter 2025

January 21, 2025 We’ve rounded up some great opportunities for accessibility research, funding, and training. Most notably, deadlines are approaching for two CREATE grants: ACM CHI Workshop on Aging in Place call for participation The ACM CHI workshop on Technology Mediated Caregiving for Older Adults Aging in Place focuses on research around technological supports for caregiving, specific to older adults as they age and begin to experience cognitive changes. See also

Access Board’s Preliminary Findings on AI and People with Disabilities

January 21, 2025 The Access Board is an independent federal agency that promotes equality for people with disabilities (PWD), including the development of accessibility guidelines and standards. Created in 1973 to ensure access to federally funded facilities, the Access Board is now a leading source of information on accessible design. In 2023, a presidential executive order tasked the Access Board with examining the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of AI. CREATE leadership and other experts consulted The Access…

How an assistive-feeding robot went from picking up fruit salads to whole meals

November, 2023 Training a robot to feed people presents an array of challenges for researchers. Foods come in a nearly endless variety of shapes and states (liquid, solid, gelatinous), and each person has a unique set of needs and preferences. A team led by CREATE Ph.D. students Ethan K. Gordon and Amal Nanavati created a set of 11 actions a robotic arm can make to pick up nearly any food attainable by fork. In tests with this set of actions,…

UW News: Can AI help boost accessibility? CREATE researchers tested it for themselves

November 2, 2023 | UW News Generative artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT, an AI-powered language tool, and Midjourney, an AI-powered image generator, can potentially assist people with various disabilities. They could summarize content, compose messages, or describe images. Yet they also regularly spout inaccuracies and fail at basic reasoning, perpetuating ableist biases. This year, seven CREATE researchers conducted a three-month autoethnographic study — drawing on their own experiences as people with and without disabilities — to test AI tools’ utility for accessibility. Though researchers…

Recommended Reading: Parenting with a Disability

October 16, 2023 Two recent publications address unnecessary challenges faced by parents with disabilities and how those challenges are made extraordinary by a legal system that is not protecting parents or their children. Rocking the Cradle: Ensuring the Rights of Parents with Disabilities and Their Children The National Council on Disability report finds that roughly 4 million parents in the U.S. who are disabled (about 6% of parents) are the only distinct community that must struggle to retain custody of…

Research at the Intersection of Race, Disability and Accessibility

October 13, 2023 What are the opportunities for research to engage the intersection of race and disability? What is the value of considering how constructs of race and disability work alongside each other within accessibility research studies? Two CREATE Ph.D. students have explored these questions and found little focus on this intersection within accessibility research. In their paper, Working at the Intersection of Race, Disability and Accessibility (PDF), they observe that we’re missing out on the full nuance of marginalized…

CREATE’s Response to Proposed Digital Accessibility Guidelines

October 4, 2023 CREATE has submitted a response, in collaboration with colleagues within the UW and at peer institutions, to the U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) proposal for new digital accessibility guidelines for entities that receive federal funds (schools, universities, agencies, etc.). The DoJ proposal invited review of the proposed guidelines. The response commends the Department of Justice for addressing the issue of inaccessible websites and mobile apps for Title II entities through the approach proposed through the Notice of…

People with Disabilities are a Population with Health Disparities

September 29, 2023 In September 2023, the Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities announced the designation of people with disabilities as a population with health disparities. The designation is one of several steps National Institutes of Health (NIH) is taking to address health disparities faced by people with disabilities and ensure their representation in NIH research. Dr. Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, in consultation with Dr. Robert Otto Valdez, the Director of the Agency for Healthcare Research…

Your Review & Comments Wanted: Proposed Federal Accessibility Standards

August 11, 2023 A proposal for new digital accessibility guidelines for entities receiving federal funds was released for review by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) on August 4, 2023. Anyone affected by these guidelines has 60 days — through Tuesday, October 3, 2023 — to comment. The DOJ is still trying to decide details, such as how quickly public entities should comply and what exceptions to allow. For example, the current rule states that course content posted on a…

Proposed Federal Accessibility Standards: CREATE’s Guide to Reviewing and Commenting

A proposal for new digital accessibility guidelines for entities receiving federal funds was released for review by the U.S. Department of Justice on August 4, 2023. Anyone affected by these guidelines had until October 3, 2023 to comment. August 2023 announcement Note that the comment period has ended. The U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) is proposing new requirements for digital accessibility for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Their goal is to provide public entities with clear and concrete standards…

CSE course sequence designed with “accessibility from the start”

March 8, 2023 The CSE 121, 122, and 123 introductory course sequence lets students choose their entry point into computer science and engineering studies, whatever their background, experience, or confidence level. And, as part of the effort to improve diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA), the courses were designed with “accessibility from the start.” A member of the course development team was a dedicated accessibility expert, tasked with developing guidelines for producing accessible materials: using HTML tags correctly, providing alt…

Honoring Judy Heumann’s outsized impact

Judy Heumann — disability activist and leader, presidential advisor to two administrations, polio survivor and quadriplegic — passed away on Saturday, March 4. Heumann’s family invited the community to honor her life at a memorial service and burial that is now available on video with ASL, captioning, and English interpretation of Yiddish included. Who was Judy Heumann? Judy Heumann fought for disabled rights and against segregation. She led the “longest nonviolent occupation of a federal building in American history,” according to the New…

Increasing Data Equity Through Accessibility

Data equity can level the playing field for people with disabilities both in opening new employment opportunities and through access to information, while data inequity may amplify disability by disenfranchising people with disabilities. In response to the U.S. Science and Technology Policy Office’s request for information (RFI) better supporting intra- and extra-governmental collaboration around the production and use of equitable data, CREATE Co-director, Jennifer Mankoff co-authored a position statement with Frank Elavsky, Carnegie Mellon University and Arvind Satyanarayan, MIT Visualization…

CREATE + I-LABS: focus on access, mobility, and the brain

A new research and innovation partnership between CREATE and the UW Institute of Learning and Brain Sciences (I-LABS) focuses on access, mobility, and the brain, especially how early experiences with mobility technology impact brain development and learning outcomes.

CREATE Submits RFI on Disability Bias in Biometrics

CREATE’s response to the Science and Technology Policy Office’s request for “Information on Public and Private Sector Uses of Biometric Technologies”

Research Workshop for Undergraduates with Disabilities

CREATE and UW AccessComputing co-sponsored a 3-day research-focused workshop for undergraduates in computing fields who have disabilities.

Education: Accessibility and Race

The Fall 2020 CREATE Accessibility Seminar focused on the intersection of Race and Accessibility. This topic was chosen both for its timeliness and also as part of CREATE’s commitment to ensure that our work is inclusive, starting with educating ourselves about the role of race in disability research and the gaps that exist in the field.

Mankoff wins AccessComputing Capacity Building award

December 16, 2020 Through her leadership, the SIGCHI Executive Committee now has adjunct chairs for accessibility, which institutionalizes accessibility as an important facet of SIGCHI activities. Jen holds monthly online meetings of the AccessSIGCHI leadership team to help set and execute its agenda. Every year AccessComputing honors someone with the AccessComputing Capacity Building Award for their work and accomplishments that have changed the way the world views people with disabilities and their potential to succeed in challenging computing careers and activities. Excerpted from an…

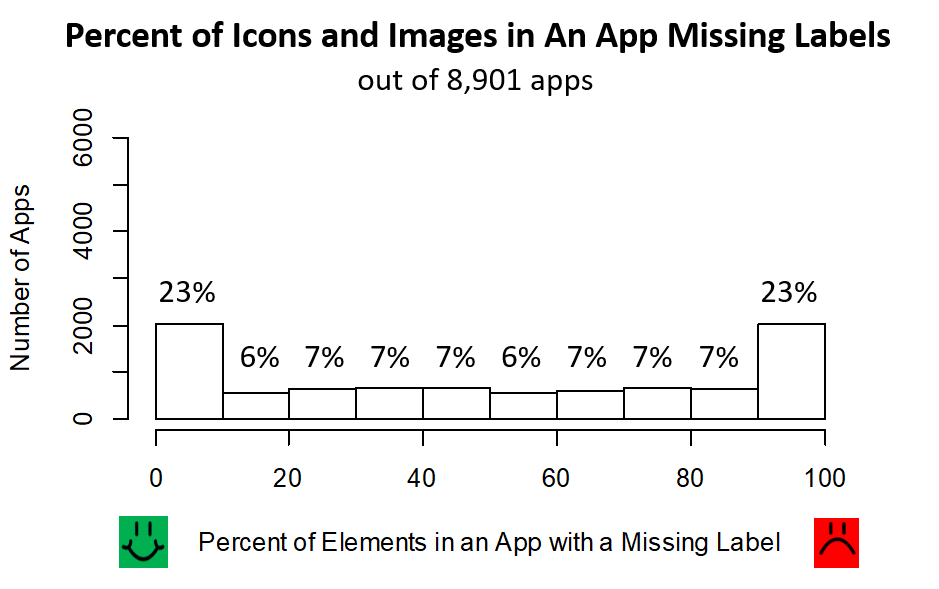

An app for everything, but can everyone use it?

Medium | May 26, 2020 For most of us, the day seems to revolve around our phones: check email, read the news, pay bills, and get directions to the store. Mobile apps are essential in day-to-day life. Unfortunately, many apps fail to be fully accessible to people with disabilities or those who rely on assistive technologies. As one blind app user noted, using an inaccessible app is “a constant feeling of being devalued. It doesn’t matter about the stupid button that…